The Forum has been conceived at a time when the issue of organised crime is prevalent in the lives of Latin Americans and largely absent from local print newspapers. Why is this the case?

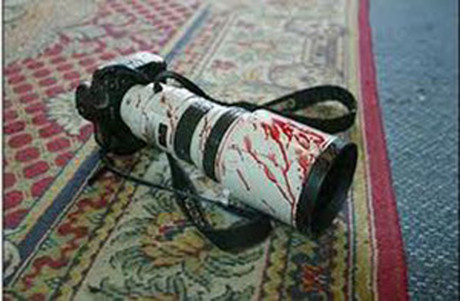

Local traditional media are more vulnerable, so their reporting is consequentially limited when covering organised crime. Take, for example, the recent firefight between one the biggest drug cartels and local police at a football match in the provincial town of Torreón, Mexico. Debates erupted in the local daily El Siglo del Torreón over whether to publish details of the story or not. Concerns over journalists’ safety played a big role in the debate, as attacks against the newspaper’s offices and its journalists - who have received death threats - were a serious consideration. According to an investigation by Ana Arana And Daniela Guazo from Fundacion Mepi, the newspaper ultimately decided to publish the story, but ommitted contextualising the shootout in relation to drug trafficking.

This is a common dilemma amongst Mexican and Latin American publications who are frequently forced into self-censorship because of fear of violent retribution from organised crime groups. This ultimately contributes to a news blackout in many regions. As stated in WAN-IFRA’s recent report, "A Death Threat to Freedom” (September, 2012), news blackouts are commonplace in several Mexican states, such as Tamaulipas where journalists are so vulnerable it is impossible to report on shootings related to drug violence.

But safety isn’t the only factor when it comes to self-censorship. Many traditional media are overdependent on government advertising revenue, resulting in what Daniel Eilemberg, founder and President of Animal Político called in a conversation with WAN-IFRA, “a large credibility crisis amongst traditional media.”

In an interview with WAN-IFRA, Carlos Dada, director of digital publication El Faro from El Salvador, suggested financial independence is the most important factor in the press freedom equation. Additionally, “not all digital media outlets are good. Quality is based on content,” he said. Although the digital platform is key in creating more flexibility to publish sensitive or risky information, a publication’s independence carries more weight in delivering quality journalism.

El Faro is supported in large part by advertising revenue and by grants from the Open Society Foundation. Plaza Pública, a digital publication in Guatemala, is up to 80% financed by the University of Rafael Landivar. Animal Político is supported equally by funds from private advertising and autonomous branches of the government, such as the Supreme Court and the IFE (Instituto Federal Electoral), Mexico’s electoral body.

Recognising the need for investigative coverage of organised crime in Latin America, Insight Crime based out of Washington D.C., approached Animal Político, Plaza Pública, El Faro and Colombia’s Verdad Abierta to tackle the various forms it takes in each of these countries. Alejandra Gutiérrez (Plaza Pública) reported on the intricate networks of sexual slavery in Guatemala, how local police and government officials were frequently involved. Animal Político uncovered how drug cartels in Mexico kidnap impoverished women and children and also white collar workers. Reporter Óscar Martínez (El Faro) interviewed victims of sexual slavery to uncover how many of these women had been tricked into the trade. For Daniel Eilemberg (Animal Político), these investigations contribute to the goal all forms of journalism should strive for: “a more informed citizenship, transparency, [and] accountibility of public officials.”

The profile of the journalists who conducted these investigations differs between publications. At Plaza Pública and El Faro, almost all journalists made the transition from print media to digital. At Animal Político, however, Eilemberg stated that around three-quarters of its staff grew up with digital and social media, making their experience in journalism exclusively digital.

As representatives from each organisation came together at the Forum, the value in “sharing experiences” across digital investigative reporting was key, asserted Alejandra Gutiérrez, speaking to WAN-IFRA. Moreover, if the issue of organised crime, especially drugtrafficking, is by nature a “transnational” issue, the possibility of exploring collaboration between Latin American digital publications is a real alternative in the future. It also suggests a viable option for how journalism could be conducted in dangerous areas.

However, in countries with low Internet penetration, where the percentage of the population who can access the Internet can be as low as 20%, just how much impact can these digital publications truly have? Despite El Salvador’s dismal connection rate, Dada insists that El Faro is read by a wide variety of middle class professionals in the country, and has become an international resource for those who can impact change. For Animal Político’s Daniel Eilemberg, it’s a question of publishing for the sake of demonstrating the need for this kind of coverage.

Ultimately, these publications put pressure on traditional media to report on organised crime in Latin America. They also open up the debate in the public sphere to figure out the best course of action to reverse the trend of social marginilasation that pushes people towards organsied crime.

Given the wide spectrum of backgrounds and experiences of participants at the Forum, it inevitably shed light on the “different challenges” and approaches to “models and markets,” explained Eilemberg. Despite these differences, the Forum served as a concrete base for digital publications who need to work in solidarity to cover increasingly dangerous and complex issues that affect all of Latin America.

Follow this link to watch highlights of the Forum on YouTube.