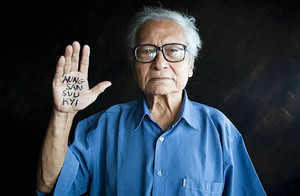

U Win Tin, a prominent Burmese editor and close political aide to Aung San Suu Kyi, died on 21 April at the age of 85. His funeral is today.

(Photo: copyright © James Mackay / ENIGMA IMAGES)

I met the-then 84 year-old U Win Tin at the end of May 2013, having been sent on a special mission to Myanmar to deliver WAN-IFRA’s Golden Pen of Freedom - a prize he’d won twelve years previously, but never had the opportunity to collect. At the time of being named WAN-IFRA’s press freedom hero along with fellow journalist San San Nweh, Win Tin was a little over half way through a 20-year jail sentence.

Sitting under a large ceiling fan in the high-beamed sitting room of a house on the outskirts of Yangon, we ate cakes and drank sodas while he gave me his take on the recent transitions in Myanmar.

Occasionally, at the behest of the half-a-dozen or so journalists who sat in with us, we paused for photographs, at which point Win Tin adopted a stern, defiant glare into the lens as if daring it to snap his portrait. Otherwise, for the duration of our meeting, he barely let up his huge smile, unless it was to laugh out loud and grab my arm, telling me “listen, you must know this.”

We talked over Myanmar’s recent transformation, the incredible speed at which ‘civilian’ government had replaced the military, and the phenomenon of washing machines and flat-screen TVs that now burst out of the stores on Sule Pagoda Road where, only a matter of 18 months ago there had literally been nothing to buy. “Things have certainly improved, but these so-called changes in democracy, human rights, etc., just aren’t profound enough,” he warned.

As a prominent journalist, writer and senior member of the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD), Win Tin served nineteen years of a twenty-year prison term after being sentenced on three consecutive occasions. For much of this time he was held in solitary confinement.

On 23 September 2008, at the age of 79, the military Junta finally released him as part of an amnesty for political prisoners ahead of 2010 elections. As a result, he had the notoriety of being Burma’s longest-serving political prisoner.

“They released me because I am old, not because I was innocent,” he told me, the infamous prison blues that he continued to wear a sign that his indignation had not waned. “I’ll take them off when they finally decide to remove all the charges.”

As former chief-editor of Hanthawathi newspaper, over the years Win Tin wrote many articles that were critical of the Burmese regime, and for which he eventually paid dearly. He had also been a close political advisor to Nobel Peace Prize laureate and Burmese opposition leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and was considered by many as her right-hand-man.

But despite his affiliation to the NLD (a party he helped found) and its celebrated leader, his open criticism of Suu Kyi for her conciliation with former Junta leaders came from a fierce sense of defiance that, until the end, never deserted him.

“When it comes to the ‘civilian’ government, in reality we are dealing with the same faces. Building trust will take time.”

As I prepared to leave, Win Tin’s aides seemed overly eager to show me what appeared to be little more than a lean-to shack, half-hidden at the bottom of the garden. As the veteran journalist said his goodbyes from the relative cool of the ventilated main house, I climbed into the sticky midday heat to see what all the fuss was about. “This is Win Tin’s house,” the man leading me gleefully revealed as we stooped through the doorway. I was dumbfounded.

It turned out that Win Tin effectively squatted in his friend’s back garden. After losing his own house and having most of his possessions confiscated, his few books, paintings and a writing desk were all that remained. The money he received from donors and well-wishers he invested entirely into his foundation to help the families of political prisoners.

Despite the spectacle of having such a venerated elder statesman of the Burmese press live in what was little more than a garden shed, his aides insisted he was more than happy: Win Tin had apparently refused countless offers of an upgrade, saying he had everything he needed. And strangely, the scene befitted the man, surely one of the humblest of a generation of countless brave men and women persecuted for their belief in freedom.

Only one thing seemed oddly out of place. Affixed to the wall above his desk, opposite a little cot bed, a giant flat screen TV - so that he could watch his beloved Manchester United.

Indeed, change had come to even the most unexpected of corners.

The Golden Pen of Freedom is WAN-IFRA's annual award recognising individuals or organisations that have made an outstanding contribution to the defence and promotion of press freedom. Established in 1961, the Golden Pen of Freedom is presented annually and is amongst the most prestigious awards of its kind throughout the world. Behind the names of the laureates lie stories of extraordinary personal courage and self-sacrifice, stories of jail, beatings, bombings, censorship, exile and murder. They are the true heroes of the struggle for press freedom worldwide.

In 1963 WAN-IFRA awarded the Golden Pen of Freedom to Burmese journalist U. Sein Win. In 2001 the organisation jointly awarded U Win Tin and San San Nweh, and in 2013, the award was given to Dr. Than Htut Aung, CEO of Eleven Media Group.

The 2014 laureate is jailed Ethiopian journalist Eskinder Nega. For more information visit http://www.wan-ifra.org/microsites/golden-pen-of-freedom